In architectural design practice, the first thing that comes to mind to implement diversity and inclusion is "barrier-free" design. "The Act on Promotion of Smooth Transportation, etc. of Elderly Persons, Disabled Persons, etc.," commonly known as the Barrier-free Law, stipulates standards for the development of buildings and public spaces. The design process must comply with detailed criteria for architectural components such as corridor and staircase dimensions, gradients, railings, and toilets. To this day, the design process has often focused primarily on developing architectural components in compliance with the standards.

Chika Sakamoto, one of Kume Sekkei's employees, became the first Japanese woman to compete in the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics in Para Powerlifting. She has noticed and experienced various issues and challenges when accessing buildings and cities from the standpoint of a wheelchair user. We wanted to create opportunities for designers to share the experiences of the parties concerned, and apply them to architectural and urban planning in the future. With this in mind, we started the Barrier-Free Design Experience and Verification for Architecture and Towns, to shift from "criteria-centered barrier-free design" to "barrier-free design with the user at the center". We visited the buildings we have designed with Ms. Sakamoto and other project architects to verify the results of our work. We have extensively verified hotels, restaurants, offices, commercial facilities, parking lots, public transportation, and public spaces in cities.

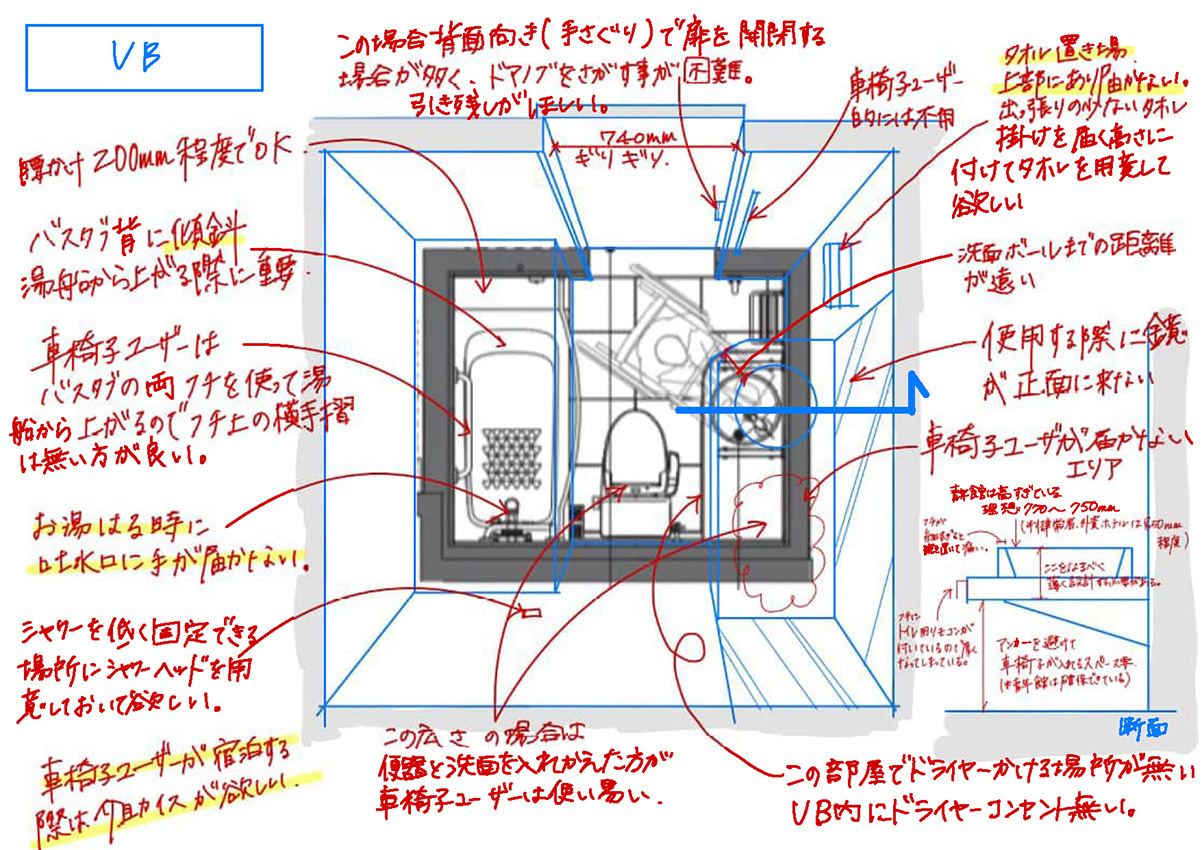

The architects also rode in a wheelchair and underwent each experience from the same perspective and with the same movements as Ms. Sakamoto. We all discussed on the spot what we had noticed and how we could make it easier to use.

For example, barrier-free routes are often inadequately navigated although they are designed and provided according to the law; Simply making the restroom handrails in easily visible colors will improve usability; Wheelchair drivers are often unable to use the wheelchair user parking spaces because colored cones are placed there to prevent general vehicles from parking, which are difficult for them to remove; Simply providing movable furniture in hotel rooms will make it easier to optimize the arrangement to suit the user's situation; Natural position (a position that a wheelchair user can reach in a comfortable, effortless manner) is essential, and so on. Naturally, experiences will vary depending on the type and degree of disability. However, by experiencing them with a wheelchair user, the architects were also able to experience firsthand the usability and safety of these buildings, and it allowed them to think about effective designs that would ensure usability and safety for as many people as possible.

Facility operators were present at several facilities where we conducted our inspections. They listened attentively to our lengthy discussions. Ultimately, the architects compiled improvement plans from tangible and intangible perspectives to address the issues they found during the verification and advised the operators. The operators commented, "This is very helpful. We will start taking action tomorrow where we can." We hope to further promote the practice of barrier-free design from the user's point of view rather than the conventional approach of barrier-free design adhering to standards and manuals. We are also beginning to verify buildings during the design phase. We would also like to advise on operations and initiatives that lead to sustainable activities and attitudes that involve the community and users. Kume Sekkei is committed to addressing diversity and inclusion in architecture and cities from various perspectives.